DEVOTION

These recreated altars, one from Nepal and the other from Japan, offer glimpses into the intimate worlds of Buddhist practice. Drawn from personal domestic settings, they reflect the distinct material cultures that devotees have gathered over time—objects shaped by lived histories.

Devotion here unfolds across the senses—the rhythmic beat of the drum, the chime of the bell, the drifting scent of incense, the flicker and warmth of candlelight, the textured feel of prayer beads between fingers. These multisensory elements draw the body and spirit into a daily choreography of reverence.

Placed side by side, these altars reveal both the diversity and resonance of Buddhist traditions across Asia. The objects, gestures, and symbols may differ, shaped by regional histories and practices. Yet, in their shared atmosphere of care and presence, they speak to a common thread of devotion that transcends geography.

BUDDHISM IN ASIA: AN ENCOUNTER WITH EVERYDAY OBJECTS

The exhibition is best viewed on a desktop. The mobile version does not include all the elements.

‘The sickness of bodhisattvas comes from their compassion for all living beings!’ This was the famous response Vimalakirti gave to Manjusri when asked about his illness. The householder saint explained that his ailment is caused by love and feelings of attachment to his fellow beings. To truly understand others, he implies, is to partake in the joy and suffering that come with every encounter. Relatedly, anthropology, from the beginning, has been a discipline defined by such encounters–moments of deep connection that require openness, empathy, and a willingness to care about the lives and material worlds of others.

Buddhism in Asia: An Encounter with Everyday Objects explores Buddhism through the lens of these multifaceted encounters. It presents objects gathered by PhD candidates during their travels and fieldworks across Asia. While the objects on display offer insight into the everyday devotional practices of Buddhist communities, the stories of their acquisition reflect how anthropological engagements with different cultures have evolved. These everyday devotional objects were borrowed, purchased, or gifted by informants. In addition to being Buddhist artifacts, they embody the chance encounters between anthropologists and the individuals, families, and communities who shared their lives and traditions. In showcasing these objects, the exhibition strikes to align with James Clifford’s concept of the museum as a ‘contact zone’, a space where different cultures converge, and collaborations replace top-down interpretation and transmission.

At the heart of this exhibition are everyday objects that may seem ordinary–prayer beads, candles, amulets, prayer books and fragments of household shrines–but each piece plays an important role in the lives of those who own and use them. These devotional objects, while part of daily routines, serve as tools for introspection, reminders of personal beliefs, or symbols of protection. Through these artifacts, the exhibition demonstrates that Buddhist practice is not confined to temples or monasteries but extends into homes, streets, and the intimate moments of daily life.

The details of the objects are further expanded online, including how they are crafted, used, and collected and so you are encouraged to scan the QR codes that lead you to our website.

Curators Lok Hang Hui, Delphine Mercier,

Mridu Thulung Rai

Objects Contributed by

Alastair Parsons

Bo Yang

Lok Hang Hui

Mridu Thulung Rai

Paula Bronson

Yuqi Wang

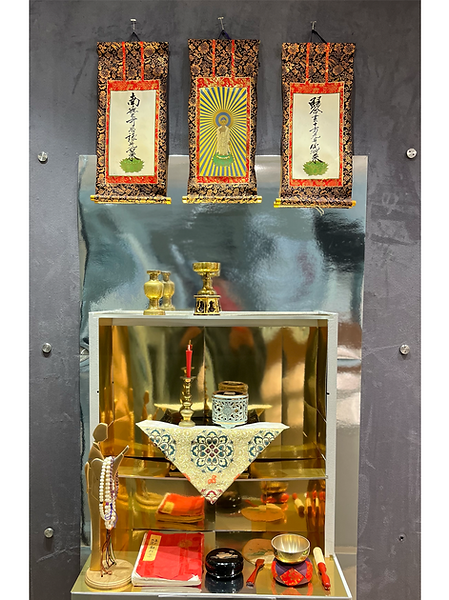

Devotional Space in Japanese Households

This display recreates the devotional space of a butsudan (仏壇), the Buddhist shrine commonly found in Japanese homes. The wooden cabinet that originally housed these objects was too damaged to be preserved after the 2024 Noto earthquake. The surviving items were salvaged from two home altars and donated by a local butsudan dealer. They reflect the Ōtani-ha tradition of Jōdo Shinshū (浄土真宗大谷派), one of Japan’s largest Buddhist schools.

At the top hang three scrolls: Amida Buddha in the centre is flanked by calligraphic inscriptions of his sacred name. The gilded background and symmetrical layout reflect the altar arrangement at Higashi Honganji, the sect’s head temple in Kyoto, and symbolically recreate Amida’s Pure Land within the home.

A butsudan typically includes two sets of ritual implements, each consisting of a candle stand, incense burner, and flower vase. A formal set, known as sangusoku (三具足), is placed inside the shrine, while the more casual set shown here is usually kept on the lower shelf for daily use.

Each implement expresses a core teaching of Jōdo Shinshū:

• Flowers represent Amida’s compassion. Thorny plants like roses are avoided, as are vines, which may symbolise over-reliance on the Buddha.

• Incense symbolises equality—its fragrance is shared by all, regardless of status or wealth.

• Candlelight represents Amida’s wisdom, illuminating the darkness of ignorance.

Contributor: Lok Hui Hang

A Special Case on

Butsudan Restoration

These before-and-after photos document the restoration of a butsudan from the town of Togi in Noto Peninsula. Measuring 110 cm wide, the altar was custom-made in the hon-sampō biraki (本三方開き) style—featuring triple-opening doors on three sides for a grand display. The enshrined scrolls bear the signature of Datsunyo (達如, 1780–1765), suggesting a long lineage of devotion.

Both the butsudan and the home it was enshrined in were severely damaged in the 2024 Noto Earthquake. Remarkably, the family sent the altar for restoration in July 2024, and the repair was completed by March 2025—months before their house is due to be rebuilt. Until then, the altar remains stored at the butsudan shop.

The story highlights the emotional and cultural significance of the butsudan in the region.

Candle Making in Post-Disaster Noto

‘We have no candles for our butsudan. Do you know where we can find some?’ Such calls began to pour in at Takazawa Candle just two weeks after the 2024 Noto Earthquake. The magnitude 7.6 tremor struck on New Year’s Day, displacing tens of thousands of people. For many families, the loss of their homes also meant the loss of their daily rituals, especially the lighting of candles on their household altars, a small but vital act that maintains connection with their ancestors. Founded in 1892, Takazawa Candle has been making traditional Japanese candles in the Noto Peninsula for over a century. Their shop, housed in a 110-year-old registered cultural property on Nanao’s Ipponsugi Street, was a well-known landmark. It too collapsed in the earthquake. This was not the first time the family business faced disaster. After two major fires in 1895 and 1905 destroyed much of Nanao’s Edo-period architecture, the family rebuilt and continued their craft. In late January 2024, just weeks after the earthquake, candle production resumed. Despite continued water and power outages, the workshop adapted by drawing well water to cool their metal moulds. Their early restart ensured that candles could once again illuminate home altars across the region.

Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism, introduced to Tibet by Guru Rinpoche (Padmasambhava) in the 8th century, blends Mahayana and Vajrayana teachings. It incorporates ritual, meditation and monastic scholarship. The four primary schools are Nyingma (the oldest and associated with Guru Rinpoche), Sakya (noted for its scholasticism), Kagyu (which emphasizes meditation lineages), and Gelug (led by the Dalai Lamas). Despite their differences, all share core teachings on compassion, emptiness, and the path to enlightenment through disciplined practice and devotion to the guru. Rooted in Indian Buddhism, it incorporates indigenous Bon elements and thrives in Tibet, Nepal, Bhutan, and across the Tibetan diasporas.

Contributor: Paula Bronson

DRUM This drum (Tibetan: choeda, Nepali: damaru) is used in a Tibetan Buddhist practice called choed, which means 'to sever'.

PRESENCE

The sacred is often experienced more through feeling than fixed definition.

The objects on display here mark a threshold—where the tangible meets the transcendent. Within the context of the contributors’ Buddhist practices, we see how everyday materials—beads, fabrics, images—are transformed into vessels through which the intangible is approached, sensed, and shared.

How do such objects help us commune with that which lies beyond the visible or tangible? How is spiritual presence felt? What does it mean to receive a blessing—or to give one? And how are these blessings carried, transferred, or held within material forms?

Rather than merely representing the sacred, these objects invite us to consider their active role—do they embody the transcendental, or do they animate it—extending its presence into daily life?

Each object on display gestures toward these questions in its own way, offering a meditation on the ways belief and matter are intertwined.

At the Threshold of Divinity

Photographed at Drakkar Monastery (བྲག་མཁར་དགོན་), in Lhagang Town, Kangding City, Garze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, China – one of my principal fieldwork sites – I hold my personal prayer beads and gaze across the valley toward the distant summit of Sacred Mount Zhagdra (བཞག་བྲ་ལྷ་རྩེ་).

In Tibetan cosmology, monasteries are sacred abodes of the Three Jewels: the Buddha, the Dharma (teachings), and the Sangha (monastic community). Sacred mountains, by contrast, are storied landscapes – sites of local oral traditions, ancestral spirits, and Bon cosmologies – often later incorporated into the Tibetan Buddhist pantheon. The prayer beads often serve as both a devotional tool and a material biography, physically worn and ritually charged. They are a personal medium of Buddhist self-cultivation, threading together body, mind, and landscape through tactile engagement with mantra, movement, and memory.

Contributed by Bo Yang

Luang Por Yai (foreground) leads her monks on thudong pilgrimage, 1963, Nakhon Ratchasima province, Thailand. Image courtesy of Wat Thamkrabok 'Special Work' archive. Original photo by Phra Prasaan Bungtitarro Bhikkhu

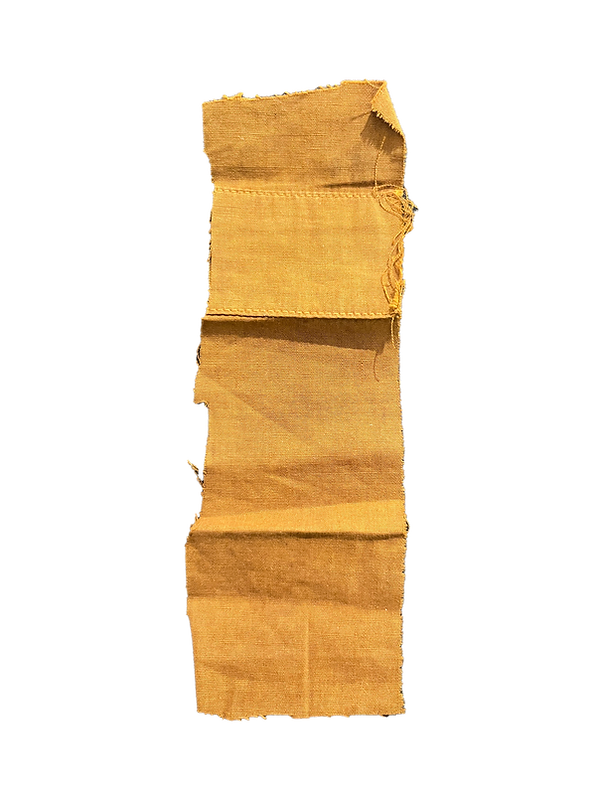

Clipping of Luang Por Yai’s Jiwon (outer monk’s robe)

Cotton fabric coloured with dye derived from jackfruit tree bark

During the early 20th century, the nascent Thai state sought to standardize Theravada Buddhism to align with its modern nation-building goals, using royally endorsed doctrines to supplant local traditions and enforcing a patriarchal hierarchy through which women still cannot be ordained as full monks. Yet, alternative approaches and charismatic figures persisted outside this standardization. Among them was Luang Por Yai (1910–1970), born Mian Panchand, who overcame poverty and alcoholism in Bangkok after having a sudden transcendent experience in the 1940s. Claiming insight into the Buddha’s path to nibbana, she developed sajja-tham (“truth teaching”), an experiential form of Buddhism.

Ordained as a mae chee (nun), she soon attracted male monk followers, which was then nearly heretical. In 1957, they founded Wat Thamkrabok in Saraburi to preserve her teachings. Though she never officially ordained as a monk, her male disciples gave her the title Luang Por (“venerable father”) and dressed her in monks’ robes. Although she died in 1970, her teachings remain central at Wat Thamkrabok, which has since become famous for its addiction therapy. These robe clippings symbolize her enduring spiritual authority and the resilience of local Buddhist innovation in Thailand.

Contributor: Alastair Parsons

Blessed Khada

This is a khada (also khata/khatag), a silk scarf printed with the Tashi Tagye, the eight auspicious symbols in Buddhism. Though rooted in the Buddhist Bhutia community, the khada is one of the most recognisable and widely used ceremonial objects in Sikkim. It transcends ethnic and religious lines—offered at weddings and funerals, in greetings and farewells, in rituals both sacred and civic.

This particular khada was gifted to me by my aunt (Angela Aunty), before I left for London in February 2021 to begin my master’s at UCL, at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. She had it blessed by a monk, offering it to me for protection and good fortune as I stepped into a new chapter.

Over time, the white fabric has gathered stains, but I’ve never washed it—afraid the blessings and its meaning might wash away too.

Contributor: Mridu Thulung Rai

Ancestral tablet

Ca.1900 – Wood, pigments

China

UCL Ethnography Collection, M. 0106

Paper offering

Ca. 2000 – Paper, plastic, pigments

China

UCL Ethnography Collection, S. 0052

Numerous objects embody the link between livings and non-livings. These two objects are not related to Buddhism, but they show another materialisation of the communication between people and the afterlife.

The tablet symbolises the spirit of a past ancestor. Placed in a domestic altar and organised per generations, tablets receive food from family members who communicate with their ancestors by burning incense.

Paper offerings are used during the Qingming Festival, the day to honour the death. After cleaning the tomb, family members offer their ancestors food, incense, and paper offerings which are burnt on the tomb and received by the ancestors in the afterlife.

TRANSLATIONS

Statues, postcards, accessories, decorative magnets—souvenirs like these often travel far from the sacred sites where they were first encountered. In tourist markets across regions, spiritual symbols are reproduced, repackaged, and circulated as commodities. But what happens to their meaning in the process?

These objects sit at an uneasy intersection between devotion and commerce. For some, they are keepsakes. For others, they may still carry spiritual resonance, used in personal rituals or displayed with reverence. Their meanings are not fixed; they shift depending on context, intention, and relationship.

Rather than dismissing these items as inauthentic or merely decorative, this display invites us to consider how spiritual value is made, transferred, or lost. Can an object mass-produced for tourists still hold sacred presence? And what might that say about the ways Buddhism travels—across geographies, economies, and imaginations?

Buddhist-Themed Cultural Souvenirs after Decommercialisation Drive on Mount Jiuhua

These objects represent a new genre of cultural and creative tourism products commonly found at Mount Jiuhua, emerging in response to the state-led campaign to regulate the commercialisation of religion. Drawing on Buddhist imagery and motifs, they are redesigned and repackaged to appeal to urban consumer tastes, and are sold in both official and privately operated souvenir shops around the mountain.

They reflect the rise of a new commercial pattern shaped by policies of Buddhist de-commercialisation, and more broadly, the ongoing transformation of China’s sacred religious sites into spaces of intangible cultural heritage and cultural-tourism industries.

Contributor: Yuqi Wang

10

Cinnabar Prayer Beads

Inspired by traditional Buddhist counting beads used for chanting, this contemporary version adopts more affordable materials and a fashionable design. It is now widely worn in China as a decorative item with spiritual overtones.

Ksitigarbha Protection Charm

Based loosely on Buddhist amulets that require temple blessing, these mass-produced charms mimic the appearance of Japanese omamori. Different variants are labelled according to specific forms of “blessing” (e.g. for success, education, or wealth), catering to consumer needs.

Diting Miniature Pendant

Diting (谛听) is a mythical beast in both Buddhism and Chinese folklore, traditionally regarded as the companion of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva. While often placed beside Ksitigarbha altars in temples, local legends at Mount Jiuhua depict it as a white dog that followed the Monk Dizang from Silla. This cute miniature adopts a composite iconography—tiger’s head, rhino horn, dog ears, dragon body, lion’s

Mount Jiuhua Temple Refrigerator Magnets

These magnets feature stylised images of Huacheng Temple, the founding temple of Mount Jiuhua’s Buddhist tradition. Elements include its architectural outline and imperial plaques once granted by emperors that read “The Sacred Realm of Mount Jiuhua”(九华胜境), here transformed into sleek consumer souvenirs.

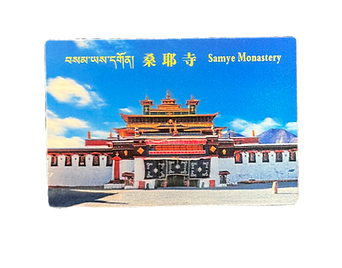

Admission Ticket to Samye Monastery (བསམ་ཡས་དགོན་པ), Tibet Autonomous Region, China

Samye Monastery is Tibet’s first monastic institution, established in the 8th century under King Trisong Detsen with guidance from Śāntaraksita and Padmasambhava. As the birthplace of monastic ordination, it marks a foundational moment in the institutionalisation of Tibetan Buddhism.

This ticket grants access but also signifies the transformation of Tibetan religious life into cultural tourism. Its pricing policy reveals tensions around ethnicity, belief, and governance, reflecting the complex entanglement of spirituality, heritage and the contemporary politics of pilgrimage.

Contributor: Bo Yang

Xiao Lao Shi (小老师): A Language Primer for Monastic Education, Kham Tibet, China

This educational booklet, titled Xiao Lao Shi (Little Teacher), is designed as a basic Mandarin Chinese learning tool for Tibetan monks, particularly novices in monastic institutions.

The book reflects shifts in Tibetan monastic education, where Mandarin is integrated into traditional curricula. For monks, it enables navigation of a Sinicizing public sphere and bureaucracy; for Han Chinese laypeople drawn to Tibetan Buddhism, it facilitates spiritual access.

Contributor: Bo Yang

The Navakovada Despite its marginal beginnings, since 2012, Wat Thamkrabok has been included as part of the Thai National Sangha. This has seen the more standardized, “national” Buddhism of Thailand become more present in daily life there, even while sajja-tham and the veneration of its unique monastic lineage remains. This text, the navakovada, is representative of that influence, and is now issued to all Thamkrabok monks upon ordination. Originally published in 1898 in Thai, it was compiled by Prince Wachirayan – the 10th Supreme Patriarch of Thailand and member of the Chakri dynasty – to help standardize and modernize Thai Buddhism. This version, published by the Thai national sangha, is translated into English in response to growing foreign interest and participation in Buddhist monastic practice, itself an indication of the influence of globalization on Buddhism in Thailand. The navakovada was largely a response to the phenomenon of short-term monastic ordination in Thailand, which remains a common rite of passage for middle-class men, and is meant to serve as a reference guide for monastic conduct for those with less time to learn its particulars. Unlike sajja-tham’s focus on individually-realized truths and analytical practice, orthodox Thai Buddhism places considerable emphasis on the Vinaya precepts – the 227 rules for monastic conduct upheld by all ordained monks – as a means to attaining Buddhist insight and the possibility of transcendence. While the Vinaya precepts are important at Wat Thamkrabok, they are seen by many more senior monks there as the behaviors one must uphold to be recognized by laity as paradigms of Buddhist virtue. That is to say, they are part of the office of the religious professional – rules established by Gautama Buddha to govern a worldly sangha – but are not fundamentally the means to enlightenment. While some might be inclined to see the presence of the navakovada at Wat Thamkrabok as evidence of the incursion of a more conservative Buddhism there, this attitude highlights the way in which, as a lived reality, Buddhism in Thailand is often as reflective of individual practitioners as it is codes and doctrines, regardless of monastic affiliations. If the standardization of Buddhism in Thailand was itself largely a response to the incursion of European colonial powers into Southeast Asia, along with their governmental and religious institutions, then the technologies of that standardization often obscure the diffuse and inclusive attitudes that define individual relationships to Buddhism, no matter where they take place in the Kingdom. Contributed by Alastair Parsons

Book of sajja vows in Thai and English

Sajja-tham, developed by Luang Por Yai, is not primarily a doctrine but a method centered on taking and practicing sajja vows. These short statements serve as starting points for personal inquiry rather than fixed rules. The core idea is that Buddhist truths are not learned from texts or teachings but realized through direct, lived experience.

Each sajja is formally undertaken through a ritual invocation with a senior monk (ajahn) for a set duration and daily time commitment. This book presents 102 sajja vows compiled by Luang Por Charoen, Wat Thamkrabok’s third abbot and Luang Por Yai’s nephew. They can be categorized as either active (behavioral) or contemplative (reflective), offering practitioners tools for both discipline and introspection. These sajja were translated by an English-speaking monk at the temple to assist foreign practitioners, many of whom are introduced to the practice after participating in the temple’s detox program.

Contributor: Alastair Parsons

Souvenirs from Higashi Honganji, Kyoto – Tokens brought back from visits to the head temple of Jōdo Shinshū Ōtani-ha.

Contributed by Lok Hang Hui

This photograph was gifted to me by my friend and interlocutor, Yawan Rai. Taken in 2015, it depicts Tathagata Tsal—commonly known as Buddha Park—a spiritual site and major tourist destination in the small town of Rabong, South Sikkim, India. The 130-foot statue of the Buddha forms the centrepiece of the site.

At the time, Yawan and I were working on a coffee table book commissioned by the Tsal’s committee. Though the book was completed, it was never released, due to political and bureaucratic reasons left unexplained to us. Eventually, 1,000 copies were quietly distributed to Buddhist institutions across Sikkim.

While intended for a touristic audience, we sought to infuse the book with spiritual intent—foregrounding the park’s architecture, relics, and sheda (monastic school). Its structure followed the eight auspicious symbols (Tashi Tagey) and comprised 108 pages, reflecting sacred numerology in Buddhism.

This photograph remains one of the most evocative images from the series— the deep blue of the night sky appeared spontaneously, an unplanned offering of the moment. For me, this particular print—a gift from Yawan—is, above all, a testament to friendship, to care, and to shared purpose.

Contributed by Mridu Thulung Rai

The Relic of Master Huicheng

Photographs by Yuqi Wang (2023)

IMAGE 1: The relic of Master Huicheng (慧成尚) is a whole-body relic, currently enshrined at Ganlu Temple (甘露寺) on Mount Jiuhua (九华山), and was officially recognised by local Buddhist authorities in 2005. Displayed in a sealed glass reliquary, the relic allows devotees to offer worship. Carved couplets flank the reliquary—on the right and left pillars respectively: “The moment one hears the wisdom of the Tathāgata, enlightenment is attained ” (即闻如来慧,当下菩提成)—while the horizontal inscription above reads: “Wisdom opens, vows fulfilled” (慧开愿成). A statue of Avalokiteśvara is also enshrined on the altar in front of the relic. Huicheng was ordained in 1986 at Mount Jiuhua but later returned to his hometown in Dangtu County (当涂县) to continue his monastic practice. After his passing in 2002, his body was placed in a burial jar (Image 2). Three years later, his remains were found incorrupt. With the support of his family and followers, the body was transferred to Mount Jiuhua, where it was gilded and enshrined at Ganlu Temple. A plaster replica of his body was also created by his former temple and is now similarly enshrined (Image 3). IMAGE 2: The zuohua vat (坐化缸) is a type of burial vessel used for the remains of deceased monks in Chinese Buddhism. It represents a fusion of Buddhist zuohua (坐化, meditative death) and the indigenous Chinese practice of jar burial, present in the Yellow River valley long before the spread of Buddhism. Meanwhile, Zuohua, or meditative death, refers to the passing of Buddhist monks in a cross-legged seated posture which reflects a level of spiritual attainment beyond the ordinary. It differs from lay death in two principal ways: first, the dying posture is upright and seated rather than reclined; and second, it signifies a peaceful departure, free from illness or suffering. This seated posture is also the most common presentation among Buddhist whole-body relics. IMAGE 3: This figure, locally known as the whole-body relic of Master Huicheng, is enshrined at a temple in Anhui Province, outside Mount Jiuhua. Unusually, the offering table below includes both Buddhist imagery and Daoist deities. According to my interlocutors, this is a plaster replica of the original relic. Having seen the authentic gilded body at Ganlu Temple, I found the replica visually similar, though the facial features differ slightly. There is no signage indicating it is a replica, and temple staff were largely indifferent to our visit.

Model of a Bulul

First half of the 20th century

Philippines, Ifuago artist

UCL Ethnography Collection, M.0080

A Bulul is a rice granary deity produced and used in the north of Philippines. This figurine is half the size of a traditional one, indicating that smaller Bulul are made for tourists. On the back of the figurine, the trace of a sticky label, probably its price, is still visible.